By Paul Amoroso, an explosive hazards specialist at Assessed Mitigation Options (AMO) consultancy

INTRODUCTION

This is the third article in a series examining how to develop and sustain an accurate IED threat picture to optimize understanding and ensure the C-IED efforts invested in remain effective as threats evolve. The first article titled, ‘Understanding and Threat Alignment Within a C-IED Enterprise’ emphasised understanding as a vital cross-cutting element of any C-IED enterprise, encompassing two key aspects: the threat itself and the effectiveness of the C-IED efforts invested in. The rest of this series of articles will focus on understanding the threat of IED attacks, through an IED threat picture.

To systematically understand the use of IEDs by a specific network in a given context1, it is essential to analyse IED attacks using the following key questions: what, how, where, when, who, and why. More precisely a comprehensive understanding of the following is required:

- What components make up an IED?

- Where are IED attacks likely to take place?

- When are IED attacks likely to place?

- Who is involved in IED attacks?

- Why are IEDs being employed?

- How are IEDs being employed?

This understanding can be considered the 5W+H of IEDs. This comprehensive analysis helps to attain an understanding of the threat, develop IED analysis tools, and maintain an accurate IED threat picture. By doing so, the strengths and weaknesses of the IED network can be identified, contributing to a threat aligned C-IED enterprise empowered to make informed decisions on investment in effective C-IED efforts.

Along with several future articles in The Counter-IED Report, this article will explore the 5W+H of IEDs as a process to create a flexible yet systematic approach for developing and maintaining an IED threat picture. It examines one of the previously mentioned methods of IED classification2 – technical components as a means to explore the first question of the 5W+H, ‘what components make up an IED.’

Understanding the IED components in use is vital to informing multiple C-IED efforts involved in any C-IED enterprise. Most notably, this will inform the most appropriate IED defeat the device capabilities that need to be invested in, developed and sustained. It will also be the most vital information around which all efforts to control IED components will be based. We will explore how this question can be addressed by recognizing that different levels of detail may be applied when answering it. A progressively detailed examination of IED components will be structured using three simple mnemonics, each providing a simple memory aid to assist in systematic profiling of IED components. Each mnemonic provides an increasingly comprehensive framework for IED technical component categorisation, the simplest being PIES, followed by SPICE, with PIECES being the most comprehensive. This examination involves a journey through PIECES of SPICE PIES. We will first examine a question often asked by many when initially being briefed on the threat posed by IEDs, ‘what does an IED look like?’

WHAT COMPONENTS MAKE UP AN IED?

A recurrent question often asked when briefing or delivering training to those involved in various C-IED efforts, is ‘what do IEDs look like?’ In many cases the audience are not C-IED specialists but from law enforcement, first responders, all-arms military units, borders and customs control, local international NGOs, government officials, members of the judiciary and even IED affected communities.

Examining how to address this question without creating false awareness through overly specific or prescriptive descriptions is a crucial starting point. The answer provided by this author to date has been that an IED most likely resembles its container,3 which, due to its improvised nature, can take on an almost limitless variety of items. This highlights the significant challenge in systematically classifying the technical components of IEDs, a challenge rooted in their inherently improvised nature, in that an IED can in theory be constructed from a vast array of components.

PIES

The basic components needed for any IED involve some explosive train, a switch to cause it to function and typically a power source.4

The explosive train will typically involve both a main charge and an initiator. This provides the basis components of most IEDs, to typically include explosives, an initiator, one or more switches, and a power source. These four components can be arranged to make the mnemonic PIES, referring to Power source; Initiator; Energetic materials;5 and Switches – both firing and arming if present.

An online graphic6 outlining the components of an IED – in this case the term initiating system is used to describe the switch, initiator and power source.

Under each of the technical headings of power sources, initiators, energetic material and switches various further classification is possible, leading to a hierarchy of technology7 As a basic example, the type of firing switch, can be further classified as command, time, victim operated or hybrid.8 This concept of a hierarchy of technology can be applied to categorizing the components of IEDs by organizing them into levels based on their functionality, complexity, and importance within the device. This approach helps in systematically analysing and understanding the construction of IEDs, providing clarity to their diverse and improvised nature. A systematic and detailed classification system of how power sources, initiators, energetic material and switches can be further categorised, along with extensive examples, is provided in ‘The IED Incident Reporting Guide,’ 6th Edition,9 and also reproduced in Annex A – Lexicon of the UN IED Threat Mitigation Handbook, Second Edition, 2024.

SPICE

When we consider the components accounted for under the PIES headings, we may return to the question posed earlier – what does an IED look like? The answer to which, is that it typically looks like its container. So, we may need to account for an IED’s container when considering its components. When we do this, we can use the mnemonic SPICE, standing for Switch(es), Power-source, Initiator, Container and Energetic material.

From a technical perspective, in addition to a general description of an IED,10 the key characteristics of a container that need to be captured are any aspects which contribute to the IED’s concealment or explosive effects. Concealment characteristics of an IED container refer to ‘materials used to prevent the discovery of an IED by visual inspection.’11 Explosive effects characteristics of a container refer to aspects such as:

- Confinement of an explosive main charge which may lead to a deflagration to detonation effect and is often how pipe bombs function.

- Configuration of the container to produce directed explosive effects which are considered a type of enhancement and are covered later in this article.

PIECES

While the SPICE mnemonic accounts for the main components in an IED it fails to account for components which are often of greatest interest – enhancements.12 The inclusion of enhancements leads to the mnemonic PIECES, standing for Power-source; Initiator; Energetic material; Container; Enhancements; and Switch(es).

It is acknowledged that not all IEDs have enhancements, with some IEDs producing all their explosive or incendiary effects from the main charge. An IED can be considered enhanced when additional material is integrated into the main charge, positioned in close proximity to it, or when the main charge is configured in a specific way relative to the container or added items. Enhancements are added to an IED to increase their harmful and damaging effects. The following six types of enhancements are possible:

• Blast enhancements

The blast from some common explosives can be increased by mixing certain material with them. Common terms associated with such IEDs are blast bombs and enhanced blast IEDs.

• Fragmentation enhancements

The effects of blast reduce quickly with distance from the point of initiation, with the container of an IED often producing natural fragmentation which along with other components are propelled omnidirectionally from the point of initiation often causing many of the injuries and in certain cases damage. For example, a pipe bomb propels often lethal fragmentation in the surrounding area due to the rupture and projection of the container material. The effects of fragmentation can be increased by the addition of additional often metallic material to an IED. This gives rise to such descriptors as nail bombs, ball bearing IEDs etc. Such omnidirectional fragmentation charges can cause casualties in all directions. Alternatively, fragmentation may be positioned to channel fragments into a narrower path, functioning similarly to a large shotgun, forming what is known as a Directional Fragmentation Charge (DFC) and sometimes referred to as shotgun IEDs. A variation on this design is to produce a curtain of fragmentation projected out from one side of an IED. Such IEDs are often referred to as claymore IEDs or improvised claymores. Another variation on the DFC design is a Directed Fragmentation Focussed Charge (DFFC) designed to project fragments to a point of optimal concentration some distance from the IED. This allows us to classify IED fragmentation enhancement under four sub headings as shown below.

Variation in characteristics of directional explosive effect enhancements.

• Directional explosive effect enhancements

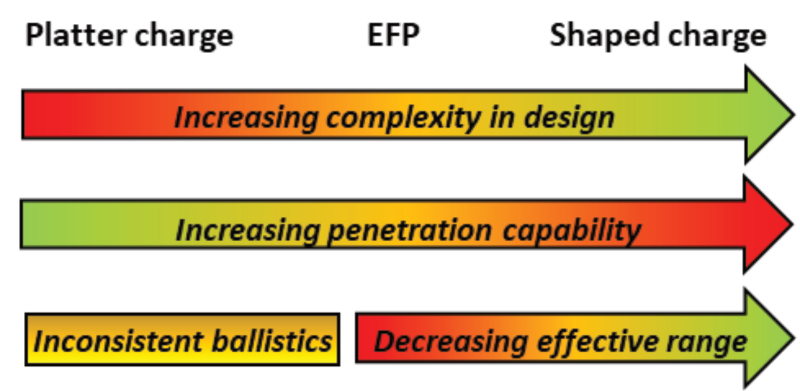

IEDs can be enhanced for the purpose of attacking armoured vehicles, including blast-resistant armoured vehicles, by the use of directional explosive effect13 enhancements. Such IEDs concentrate explosive force onto a plate, metal disk or liner which is projected at the target. They can have various degrees of technical construction from loosely fitted flat plates to well-engineered copper cones with resulting variations in complexity of design, effective range, and penetrative capability. There are three basic types of directional explosive effect enhancements:

- Platter charges;14

- Explosively formed penetrators (EFPs);15

- Shaped charges (SC).16

• Incendiary enhancements

IEDs can be enhanced by the addition of flammable liquids for the purpose of increasing casualties or starting fires in buildings. Unconfined, much of the effect of fuel enhancement will result in a fireball which will lead to thermal injuries to those within the danger area. When initiated inside a building or in close proximity to flammable material, the effects are often much more destructive than the use of explosives alone. The term blast incendiary is sometimes used to describe such devices.

• Chemical Biological & Radiological (CBR) enhancements

IEDs can be made more terrifying by adding Chemical, Biological, or Radiological (CBR) enhancements. The explosive blast of CBR- enhanced IEDs, is designed to disperse chemical, biological, or radiological substances into the surrounding area. This results in contamination of the area with toxic materials, exposing those present at the time of initiation as well as potentially those responding to such an attack. Broadly there are three categories of CBR enhancements. Those which are improvised, those which involve the use of commercial toxic materials17 and those which are military or weaponised agents.

Chemically enhanced IEDs may involve the use of improvised chemicals,18 toxic industrial chemicals19 or military grade weaponised chemicals also referred to as chemical warfare agents (CWA).20 For example, an explosive charge may be attached to cylinders of chlorine, with the intent that upon initiation, chlorine is released into the atmosphere. Attempts to use the CWA mustard gas (sulphur mustard)21 have been documented as well as efforts to employ the nerve agent sarin;22 however, the development of such complex and relatively unstable CWA is not easily achieved, typically requiring specialist equipment and high-level competent chemists and engineers. This makes improvised CWA production limited in terms of quality and quantity and often restricted to certain industrial facilities and in some cases research institutes.

Radiologically enhanced IEDs may involve the use of toxic industrial radiological materials.23 The use of an IED to explosively disseminate radiological particles is often referred to as a ‘dirty bomb’.

Biologically enhanced IEDs may involve the use of toxic industrial biological materials24 or military grade weaponised biological warfare agents (BWA).25 The explosive dissemination of a biological agent is unlikely to be effective with the same challenges present for BWA production as faced with CWA production. However, this does not mean an attacker with the intent and capability will not attempt to use biologically enhanced IEDs.

The utility of the PIECES nmemonic framework for IED component identification is illustrated above, with the components shown in transit prior to assembly into an IED.

The lethality of a dispersed CBR agent in an area depends on its concentration. However, its use often has a profound psychological impact – not only on those within the immediate area but also on people beyond it, especially when news of the attack, particularly if filmed, spreads widely. CBR-enhanced IEDs are primarily designed to terrorise a target group, and it is this impact that makes them a significantly impactful category of IED compared to others.

The acronym PIECES framework is useful for classifying all the possible technical components of IEDs, recognizing that not all IEDs will include all six components. The merits of the PIECES framework lie in its applicability at both the technical level and in supporting efforts to control access to IED components.

CONCLUSION

As part of series of articles examining a methodology for the development and sustainment of an IED threat picture, we have examined the first question within the 5W+H of IEDs – what components make up an IED? Three simple mnemonic tools of increasing detail have been outlined that can be used when designing an IED database to systematically and consistently capture details of IED components in use in a structured manner. It is advocated that the PIECES framework is employed when profiling IED components, with the caveat that there is acknowledgment that not all IEDs have all six components present. The merits of the use of the PIECES framework are that it is not only applicable at technical level, but it can also support IED component control efforts. As trends and patterns of the components in use and their technical configuration emerges, device profiling is empowered which can then inform the technical complexity of the threat. Details of the technical complexity of an IED threat is one of the key components that will make up an IED threat picture. The next article in this series will examine the tactical sophistication of IEDs in use by exploring the question, ‘how are IEDs being employed?’ ■

As part of series of articles examining a methodology for the development and sustainment of an IED threat picture, we have examined the first question within the 5W+H of IEDs – what components make up an IED? Three simple mnemonic tools of increasing detail have been outlined that can be used when designing an IED database to systematically and consistently capture details of IED components in use in a structured manner. It is advocated that the PIECES framework is employed when profiling IED components, with the caveat that there is acknowledgment that not all IEDs have all six components present. The merits of the use of the PIECES framework are that it is not only applicable at technical level, but it can also support IED component control efforts. As trends and patterns of the components in use and their technical configuration emerges, device profiling is empowered which can then inform the technical complexity of the threat. Details of the technical complexity of an IED threat is one of the key components that will make up an IED threat picture. The next article in this series will examine the tactical sophistication of IEDs in use by exploring the question, ‘how are IEDs being employed?’ ■

FOOTNOTES

- Context in terms of an IED threat picture refers to both the IED system involved and the local context. The IED system is assessed under its intent, capabilities and the opportunities it has to employ IEDs against defined target(s). Local context is defined by a geographic area, the target of the attacks and other local factors.

- IED Classification – Breaking Down Bomb Attacks, The Counter-IED Report, Spring/Summer 2025.

- In most cases, the container of an IED can be any item with a void within which the other components are secreted or held. A container may also act to have some of the IED components attached to it.

- The author acknowledges that it is possible to have an IED without a power source in the traditional sense with such IEDs having been documented; however, they are rare and difficult to employ effectively, typically owing to the sensitivity of the energetic material involved.

- The term “explosives” is often used in this context to refer specifically to the main charge. However, in a broader sense, it encompasses all energetic materials in the IED, apart from the initiator. Within the PIES framework, the “E” accounts for these energetic materials, which can include high explosives, propellants, and pyrotechnic compositions. Consequently, the “E” in all three mnemonics refers to any energetic material involved.

- Images from Examining the Role of Metadata in Testing IED detection System, by Paul J. Fortier and Kiran Dasari University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, Published in the ITEA Journal 2009: 30: 421-433

- The term “hierarchy of technology” refers to the structured arrangement or classification of different technological systems, tools, or components based on their complexity, functionality, or importance. This hierarchy often highlights the relationship between foundational technologies that serve as building blocks and more advanced technologies that depend on or are built upon them.

- A hybrid IED switch refers to any switch or number of switches configured as a combination of timed and/or command and/or victim operated switches to act independently and/or dependently on each other.

- https://tripwire.dhs.gov/carousel/ied-reporting-guide-6th-edition Released January 2024.

- For example, the use of certain containers in some areas has given rise to generic descriptions based upon the container in use such as coffee jar IED.

- The IED Incident Reporting Guide, 6th Edition.

- An optional, deliberately added component or configuration of the IED as opposed to a secondary hazard which modifies the effects of the IED. The IED would be effective yet produce a different measurable result if this material or configuration was not present. The effect can be additional physical destruction, proliferation of dangerous substances (radiation, chemicals, etc.), or other results to enhance the effect of the IED. The IED Incident Reporting Guide, 6th Edition.

- A term used to describe explosive effects produced by the initiation of explosives in intimate contact with a liner which is projected forward with varying effects depending on many factors resulting in either shaped charge jets, Explosively Formed Projectiles (EFP) or platter charges.

- In a platter charge IED, the enhancement is added in the form of a flat metal plate. When the IED is initiated, the plate is projected towards the target at high velocity, often breaking into several large fragments. The plate, or fragments, may be capable of penetrating light armour at distance of a few metres.

- Also referred to as explosively formed projectiles, explosively forged projectiles and explosively forged penetrators. In an EFP IED, the enhancement is added in the form of a dish, precisely shaped from ductile metal. When the IED is initiated, explosive forces bend the dish causing it to invert. This forms a smaller more aerodynamically stable cross-sectional area penetrator that is projected towards the target at very high velocity. Depending on their design, these projectiles are capable of penetrating substantial armour at distances even beyond 10 m or so.

- Shaped charges are common in conventional munitions, often referred to as HEAT warheads. In a shaped charge IED, the enhancement often involves the addition of a copper cone. When the IED is initiated, a jet of copper is fired towards the target at extremely high velocity. Jets can penetrate very thick armour, but only if the IED is initiated in close proximity to its target.

- Generic term for toxic or radioactive substances in solid, liquid, aerosolized, or gaseous form that may be used, or stored for use, for industrial, commercial, medical, military, or domestic purposes. Toxic industrial material may be chemical, biological, or radioactive and described as toxic industrial chemical, toxic industrial biological, or toxic industrial radiological. Source: The IED Incident Reporting Guide, 6th Edition.

- This category stands apart from the use of commercial toxic industrial materials and military-grade weaponized CWA sources due to its improvised nature and reliance on non-standard or improvised components. One may consider these as analogous to improvised explosives in comparison to commercial explosives and military grade explosives.

- A chemical developed or manufactured for use in industrial operations or research by industry, government, or academia. For example: pesticides, petrochemicals, fertilizers, corrosives, poisons, etc. These chemicals are not primarily manufactured for the specific purpose of producing human casualties or rendering equipment, facilities, or areas dangerous for human use. Hydrogen cyanide, cyanogen chloride, phosgene, and chloropicrin are industrial chemicals that can also be military chemical agents. Source: The IED Incident Reporting Guide, 6th Edition.

- A chemical substance which is intended to kill, seriously injure, or incapacitate mainly through its physiological effects. The term excludes riot control agents when used for law enforcement purposes, herbicides, smoke, and flames.

Source: The IED Incident Reporting Guide, 6th Edition. - https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/06/1137492; and

https://ctc.westpoint.edu/islamic-state-chemical-weapons-case-contained-context/ - https://worldview.stratfor.com/article/sarin-shell-who-might-have-used-it; and

https://www.newsweek.com/ieds-secret-sarin-supply-129165 - Toxic Industrial Radiological (TIR) enhancement refers to any radiological material manufactured, used, transported, or stored by industrial, medical, or commercial processes. For example, spent fuel rods, medical sources, etc.

Source: The IED Incident Reporting Guide, 6th Edition - Any biological material manufactured, used, transported, or stored by industrial, medical, or commercial processes which could pose an infectious or toxic threat. Source: IED Incident Reporting Guide, 6th Ed, Jan 24.

- A microorganism or a toxinA derived from it that causes disease in personnel, plants, or animals or causes the deterioration of materiel.

NOTE A: A toxic substance produced by and derived from plants and animals or created synthetically. Source: The IED Incident Reporting Guide, 6th Edition.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Paul Amoroso is an explosive hazards specialist and has extensive experience as an IED Threat Mitigation Policy Advisor working in East and West Africa. He served in the Irish Army as an IED Disposal and CBRNe officer, up to MNT level, and has extensive tactical, operational, and strategic experience in Peacekeeping Operations in Africa and the Middle East. He has experience in the development of doctrine and policy and was one of the key contributors to the United Nations Improvised Explosive Device Disposal Standards and the United Nations Explosive Ordnance Disposal Military Unit Manual. He works at present in the MENA region on SALW control as well as in wider Africa advising on national and regional C-IED strategies. He has a MSc in Explosive Ordnance Engineering and an MA in Strategic Studies. He runs a consultancy, Assessed Mitigation Options (AMO), which provides advice, support, and training delivery in EOD, C-IED, WAM as well as Personal Security Awareness Training (PSAT) and Hostile Environment Awareness Training (HEAT). This article reflects his own views and not necessarily those of any organisation he has worked for or with in developing these ideas.

LinkedIn profile: https://www.linkedin.com/in/paul-amoroso-msc-ma-miexpe-60a63a42/

Download PDF: 33-40 Paul Amoroso article – A Journey Through PIECES of SPICE PIES – COUNTER-IED REPORT, Spring-Summer 2025

COUNTER-IED REPORT, Spring/Summer 2025